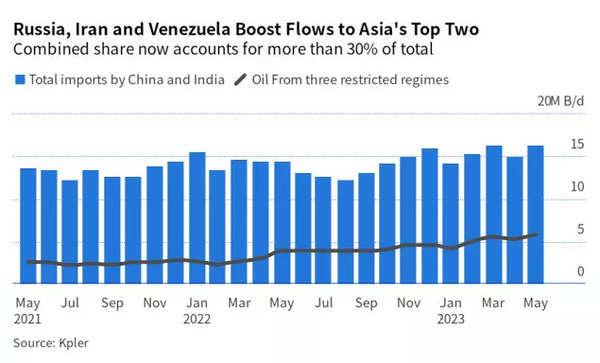

China and India took more than 30% of their combined imports from the three states in April, according to data tracked by intelligence firm Kpler. That’s up from just 12% in February 2022, the month Russia invaded Ukraine.

Exports from traditional suppliers are being squeezed. Flows to the pair from West Africa and the US have collapsed by more than 40% and 35%, respectively.

“Clearly Asian buyers are the winners here for cheap oil costs,” said Wang Nengquan, a former economist at Sinochem Energy Co. who’s worked in the oil industry for more than three decades. In recent months, Asia, led by India, has become Russia’s biggest trading partner, which has essentially helped Moscow to restore its oil exports to normality, according to Wang.

The reshaping of flows testifies to the flux in the world’s most important commodity market, where global demand runs at about 100 million barrels a day, with growth led by India and China.

After Russia’s invasion, western nations barred flows of its crude and products from their own markets and imposed a price-cap mechanism to push them elsewhere.

The complex framework, championed by US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, was designed as a way to curb the Kremlin’s income, while keeping world markets supplied.

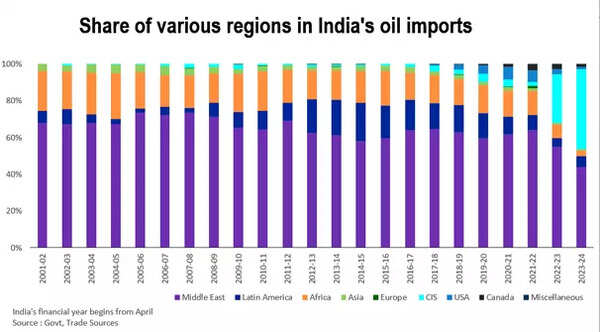

“Within Asia, almost 90% of Russia’s exports now go to these two,” Andreas Economou, Bassam Fattouh and Ahmed Mehdi wrote in a research report for The Oxford Institute For Energy Studies, referring to India and China.

While Russia has been successful in redirecting oil flows, it has lost most of its old customer base, the trio said. But with the fate of its exports now heavily dependent on just a few countries, mainly China and India, that gives refineries there “huge market power,” they said.

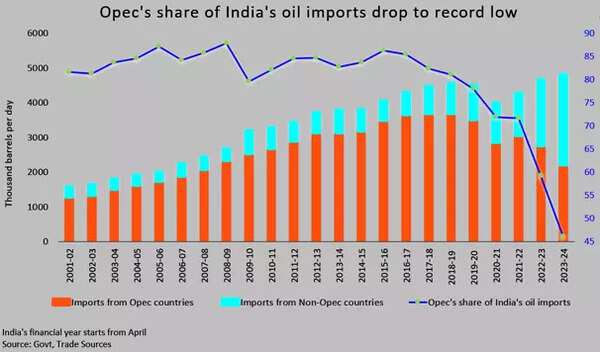

Between the two, India has had the biggest jump in appetite for Russian crude, while China has also taken a greater volume of Russian barrels and sustained purchases of Iranian and Venezuelan oil, which come with steep discounts. The US has long imposed sanctions on crude from the two nations.

Data from the International Energy Agency — the Paris-based body that advises major economies — have showed the sanctions on Russia working as intended, with Russia’s oil exports in March at the highest since Covid, yet revenue down by nearly half from a year earlier.

The US Treasury also said this month the price cap had kept barrels moving while cutting the Kremlin’s funding.

“The price cap policy is a novel tool of economic statecraft,” the Treasury, led by Yellen, said in a report. “This restriction has worked to limit Russia’s ability to profit from its war while promoting stability in global energy markets.”

The need for Moscow to keep its oil moving to markets in Asia, as well as pre-existing curbs on cargoes from Iran and Venezuela, has led to increased use a so-called dark fleet of tankers. Most of these vessels operate outside of western oversight and are aged, raising safety concerns.