Wildfires burning through large swathes of eastern and western Canada have released a record 160 million tonnes of carbon, the EU‘s Copernicus Atmospheric Monitoring Service said on Tuesday.

This year’s wildfire season is the worst on record in Canada, with some 76,000 square kilometres (29,000 square miles) burning across eastern and western Canada. That’s greater than the combined area burned in 2016, 2019, 2022 and 2022, according to the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre.

As of June 26, the annual emissions from the fires are now the largest for Canada since satellite monitoring began in 2003, surpassing 2014 at 140 million tonnes.

“The difference is eastern Canada fires driving this growth in the emissions more than just western Canada,” said Copernicus senior scientist Mark Parrington. Emissions from just Alberta and British Columbia, he said, are far from setting any record.

Scientists are especially concerned about what Canada’s fires are putting into the atmosphere — and the air we breathe.

The carbon they have released is roughly equivalent to Indonesia’s annual carbon dioxide emissions from the burning of fossil fuels.

Forests act as a critical sink for planet-warming carbon. It’s estimated that Canada’s northern boreal forest stores more than 200 billion tonnes of carbon — equivalent to several decades worth of global carbon emissions. But when forests burn, they release some of that carbon into the atmosphere. This speeds up global warming and creates a dangerous feedback loop by creating the conditions where forests are more likely to burn.

Smoke from the Canadian wildfires blanketed several major urban centres in June, including New York City and Toronto, tinging skies an eerie orange.

Public health authorities issued air quality alerts, urging residents to stay inside. Wildfire smoke is linked to higher rates of heart attacks, strokes, and more visits to emergency rooms for respiratory conditions.

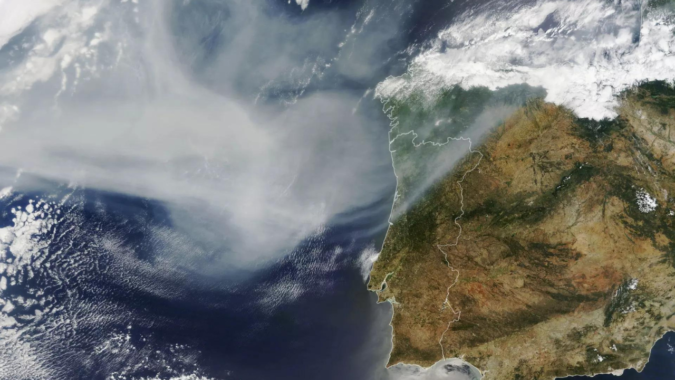

Now, the plume has crossed the North Atlantic. Worsening fires in Quebec and Ontario will likely make for hazy skies and deep orange sunsets in Europe this week, Parrington said. However, because the smoke is predicted to stay higher in the atmosphere, it’s unlikely surface air quality will be impacted.

With much of Canada still experiencing unusually warm and dry conditions, “there’s still no end in sight”, Parrington said.

Canada’s wildfire season typically peaks in late July or August, with emissions continuing to climb throughout the summer.

This year’s wildfire season is the worst on record in Canada, with some 76,000 square kilometres (29,000 square miles) burning across eastern and western Canada. That’s greater than the combined area burned in 2016, 2019, 2022 and 2022, according to the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre.

As of June 26, the annual emissions from the fires are now the largest for Canada since satellite monitoring began in 2003, surpassing 2014 at 140 million tonnes.

“The difference is eastern Canada fires driving this growth in the emissions more than just western Canada,” said Copernicus senior scientist Mark Parrington. Emissions from just Alberta and British Columbia, he said, are far from setting any record.

Scientists are especially concerned about what Canada’s fires are putting into the atmosphere — and the air we breathe.

The carbon they have released is roughly equivalent to Indonesia’s annual carbon dioxide emissions from the burning of fossil fuels.

Forests act as a critical sink for planet-warming carbon. It’s estimated that Canada’s northern boreal forest stores more than 200 billion tonnes of carbon — equivalent to several decades worth of global carbon emissions. But when forests burn, they release some of that carbon into the atmosphere. This speeds up global warming and creates a dangerous feedback loop by creating the conditions where forests are more likely to burn.

Smoke from the Canadian wildfires blanketed several major urban centres in June, including New York City and Toronto, tinging skies an eerie orange.

Public health authorities issued air quality alerts, urging residents to stay inside. Wildfire smoke is linked to higher rates of heart attacks, strokes, and more visits to emergency rooms for respiratory conditions.

Now, the plume has crossed the North Atlantic. Worsening fires in Quebec and Ontario will likely make for hazy skies and deep orange sunsets in Europe this week, Parrington said. However, because the smoke is predicted to stay higher in the atmosphere, it’s unlikely surface air quality will be impacted.

With much of Canada still experiencing unusually warm and dry conditions, “there’s still no end in sight”, Parrington said.

Canada’s wildfire season typically peaks in late July or August, with emissions continuing to climb throughout the summer.