The country is navigating through one of its worst economic crisis since independence, with inflation soaring to a near 6-decade high, food prices going through the roof and forex reserves depleting by the day.

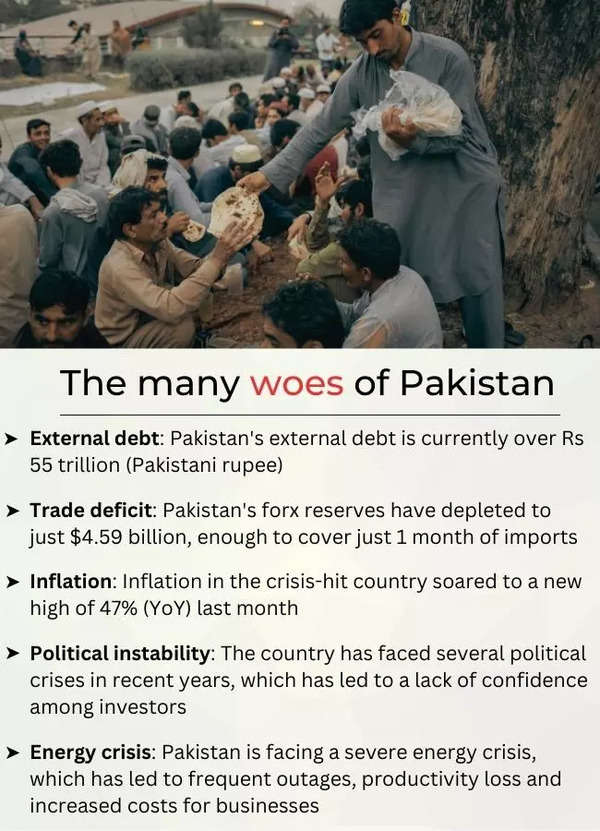

The impact of the severe economic crisis can be seen on the streets of Pakistan where poor people are seen jostling for food and queuing up in hoardes just for a bag of flour.

Not just food, even prices of gas and oil have risen sharply in recent months due to which people are struggling to make ends meet.

Long lines are forming at gas stations as prices of petrol and diesel swing wildly in the country of 220 million.

Muted Ramzan

The economic desperation among Pakistanis has played out in stark scenes across the country during Ramzan.

Since the holiday began nearly a month ago, at least 22 people have been killed and dozens injured in stampedes and long queues as people struggle to get some of the food being distributed across the country by charities and the government.

“Ramzan is for fasting, praying and celebrating, but in Pakistan, inflation has been forcing people to queue and die in stampedes to receive free food,” Muhammad Aziz, a textile worker, told The New York Times as he waited in the crowd. “It is the most expensive and unaffordable Ramzan of my life.”

As the month of Ramzan began, the inflation soared to a record 35% last month. Food inflation in March was at 47.1% and 50.2% for urban and rural areas respectively.

Due to this, the cost of chicken has now surged to Rs 350 per kilogram, while rice now costs Rs 335 per kilogram.

Similarly, mutton rates have also surged from Rs 1,400 per kilogram to Rs 1,600 per kilogram, and have eventually reached an all-time high of Rs 1,800 per kilogram.

The cost of oranges has soared to Rs 400 per dozen, bananas Rs 300 per dozen, pomegranates Rs 400, Iranian apples at Rs 340 per kilogram and strawberries at PKR 280 per kilogram.

All these prices are in Pakistani rupees.

The Pakistan government has started an initiative to provide subsidized flour during Ramzan and set up distribution points for donated flour.

But in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, mismanagement and overcrowding have plagued these efforts, local officials told NYT.

Thousands of destitute people rush daily to the distribution points, but many return empty-handed in the evening because there are not enough bags of flour to meet the soaring demand.

In Peshawar and other major cities in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, police regularly fire tear gas and charge the crowds with batons to disperse them. In some areas, enraged mobs have set upon trucks full of flour bags.

One recent afternoon, Ashraf Mohmand, a 34-year-old daily-wage construction laborer, stood anxiously outside a government distribution point in Peshawar. He said he had not received a single bag of flour, despite waiting in long lines for the past two days.

“I make just $3 a day — too little to even feed my three children,” Mohmand told NYT.

Charities struggle

Even charities are now struggling to meet the needs of starving Pakistanis.

It is during Ramzan that many Pakistanis donate their religiously prescribed yearly zakat, or alms, often giving them to charitable organizations that prepare ration packets for distribution among the poor. But this year, skyrocketing prices and the crunch on donors’ incomes have left the charities with less to distribute.

“This Ramzan, the volume of rations bags supply has drastically declined, mainly because of a decrease in donations, while the number of the destitute people approaching us has significantly increased,” Shakeel Dehalvi, an official at the Alamgir Welfare Trust, a leading charity in Karachi, told NYT.

Earlier, Reuters reported how charities across the country are facing something called a “donor fatigue”.

“Charities are struggling to deal with rising inflation and costs the same way households are. There has also been a rise in the number of people heading our way for help,” Ramzan Chhipa, founder of the Chhipa welfare association, had told Reuters.

Higher fuel prices make providing an ambulance service ever more difficult, Faisal Edhi, a philanthropist and chief of Pakistan’s largest charity operation the Edhi Foundation, said.

Mounting debt

The massive economic liabilities of Pakistan paint a grim picture for the future.

The United States Institute of Peace (USIP), a prominent think-tank, recently warned that Pakistan needs to repay a whopping $77.5 billion in external debt from April 2023 to June 2026 and the cash-strapped country may face “disruptive effects” if it ultimately defaults.

The analysis published earlier this month warned that amid skyrocketing inflation, political conflicts, and rising terrorism, Pakistan is facing the risk of a default due to its massive external debt obligations.

The USIP report called the $77.5 billion that Pakistan needs to repay in external debt from April 2023 to June 2026 a “hefty amount” for a $350 billion economy.

Notably, the Chinese debt accounts for $27 billion of the country’s total external debt. This includes around $10 billion of bilateral debt and $6.2 billion in debt provided by the Chinese government to Pakistani public sector enterprises, and Chinese commercial loans of around $7 billion.

Here’s a detailed TOI analysis on how Chinese debt has exacerbated Pakistan’s crisis.

Awaiting IMF bailout

With the economy in a shambles, the Shehbaz Sharif government is struggling to meet the terms of a 2019 deal with the IMF worth $6.5 billion and unlock a portion of those funds that have been stalled since November.

Economists say the government is in an almost impossible position.

The cash-poor country needs IMF financing to avoid default and slipping into a recession. But to meet the terms of the deal, officials must raise taxes and slash subsidies — moves that make basics like food, gasoline and utilities even more expensive for the country’s poorest.

The IMF programme, signed in 2019, will expire on June 30, 2023, and under the set guidelines, the programme cannot be extended beyond the deadline.

Pakistan and the IMF have been negotiating the programme’s resumption for months but have yet to reach an agreement.

There is no easy solution available to fix the ailing economy of Pakistan, and the government is of the view that they have taken all the tough decisions for reviving the stalled IMF programme.

(With inputs from agencies)