CANAKKALE: Facing a sea of umbrellas in the steady rain, Kemal Kilicdaroglu, the Turkish opposition’s challenger to Recep Tayyip Erdogan in next month’s polls, smiles and promises “the return of spring”.

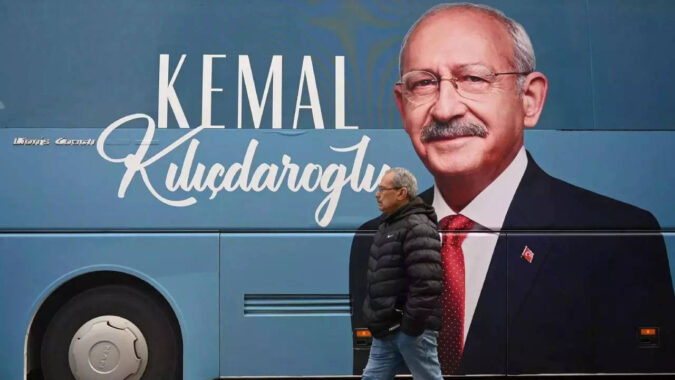

He calls the rain “pretty” even though it refuses to stop, dousing the crowd gathered in the northwestern city of Canakkale to hear the discreet 74-year-old, whose azure campaign posters announce: “I am Kemal, I am coming!”

The choice of Canakkale owes nothing to chance for Kilicdaroglu, who heads the Republican People’s Party (CHP) of modern Turkey‘s founder, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk.

It was here, at the entrance to the Dardanelles Strait, that Ataturk — then a young commander — distinguished himself in 1915 by repelling the Allied forces’ advance on the rumps of the Ottoman Empire during World War I.

“I do not order you to attack, I order you to die!” Ataturk told his troops.

Nothing that dramatic happened on stage of Kilicdaroglu’s campaign stop this week, where he was framed by the Turkish flag and portraits of Ataturk.

Kilicdaroglu emerged flanked by the two shining stars of the CHP — Istanbul mayor Ekrem Imamoglu and his Ankara counterpart Mansur Yavas — who had both unseated Erdogan’s allies in watershed municipal polls in 2019.

16 presidential planes

“Our march to power begins in Canakkale!” Yavas exclaims for stage. “We are emerging from the darkness and moving into the light.”

Trying to end Erdogan’s two-decade rule, Kilicdaroglu has united six opposition parties that includes right-wing nationalists and liberals with promises of justice, democracy, and the return of a certain political sobriety.

“I promise to sell the 16 presidential planes and I buy fire engines!” Kilicdaroglu vows from stage.

“I promise” has become something of Kilicdaroglu’s refrain, also featuring in his TV ads and social media clips.

Under her soggy white hood, Selma Ozcen, 63, sounds open to what Kilicdaroglu has to say.

“I happened to vote for the (current) government. But we want a fairer organisation, a fairer power which doesn’t trample on rights,” she says.

“We no longer want the power of a single man,” adds Rezzan Iscen, two small Turkish flags in hand.

“We must change the old system and bring democracy, justice, the rule of law. Let the economy recover. We want a life without poverty, where children do not go to bed hungry,” the former civil servant says.

“Life has become so expensive, so hard. We want a better life.”

Onions and inflation

Some in the crowd of a few thousands brandish onions, a household staple and unwitting symbol of Turkey’s eye-watering inflation, which has dropped to 50 percent from 85 percent last year, according to official figures.

Some independent economists believe the real annualised figure could be double the official one.

“I know Turkey’s problems. We all know them and we will solve them,” Kilicdaroglu says.

“We have the knowledge, the experience and the strength. This strength is you!”

Just over a month before the vote, most opinion polls give Kilicdaroglu the lead, although not one large enough to guarantee victory in the first round.

Kilicdaroglu’s path to victory is also complicated by the last-minute entry of Muharrem Ince, CHP’s candidate in the last election in 2018, who is now on course to pick up roughly five percent of the vote.

Erdogan, a veteran campaigner whose popularity has suffered from Turkey’s economic meltdown and the government’s delayed response to a February quake in which more than 50,000 died, is pledging to rebuild a “strong Turkey”.

You will win!

At the foot of the Canakkale stage, Arda Cakirer, a 20-year-old student with an earring and a thin beard, says he is “very moved”.

He will be voting for the first time in May, just like six million other young Turks who have known no leader other than Erdogan.

Cakirer appreciates Kilicdaroglu’s campaign pledge to give up power after serving out one term.

“This is very important,” Cakirer says. “After restoring order in the system, a younger president will be able to take cover.”

Sema Sur, a 40-year-old covered in a headscarf, agrees.

“If we didn’t love him, we wouldn’t have come. We’re soaked, but we love him for the sake of our future, so that hopes can flourish.”

The meeting ends, the rain stops, the umbrellas fold up and a sign brandished above the crowd’s heads looms into view.

“I promise you — you will win!” it assures the candidate.

He calls the rain “pretty” even though it refuses to stop, dousing the crowd gathered in the northwestern city of Canakkale to hear the discreet 74-year-old, whose azure campaign posters announce: “I am Kemal, I am coming!”

The choice of Canakkale owes nothing to chance for Kilicdaroglu, who heads the Republican People’s Party (CHP) of modern Turkey‘s founder, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk.

It was here, at the entrance to the Dardanelles Strait, that Ataturk — then a young commander — distinguished himself in 1915 by repelling the Allied forces’ advance on the rumps of the Ottoman Empire during World War I.

“I do not order you to attack, I order you to die!” Ataturk told his troops.

Nothing that dramatic happened on stage of Kilicdaroglu’s campaign stop this week, where he was framed by the Turkish flag and portraits of Ataturk.

Kilicdaroglu emerged flanked by the two shining stars of the CHP — Istanbul mayor Ekrem Imamoglu and his Ankara counterpart Mansur Yavas — who had both unseated Erdogan’s allies in watershed municipal polls in 2019.

16 presidential planes

“Our march to power begins in Canakkale!” Yavas exclaims for stage. “We are emerging from the darkness and moving into the light.”

Trying to end Erdogan’s two-decade rule, Kilicdaroglu has united six opposition parties that includes right-wing nationalists and liberals with promises of justice, democracy, and the return of a certain political sobriety.

“I promise to sell the 16 presidential planes and I buy fire engines!” Kilicdaroglu vows from stage.

“I promise” has become something of Kilicdaroglu’s refrain, also featuring in his TV ads and social media clips.

Under her soggy white hood, Selma Ozcen, 63, sounds open to what Kilicdaroglu has to say.

“I happened to vote for the (current) government. But we want a fairer organisation, a fairer power which doesn’t trample on rights,” she says.

“We no longer want the power of a single man,” adds Rezzan Iscen, two small Turkish flags in hand.

“We must change the old system and bring democracy, justice, the rule of law. Let the economy recover. We want a life without poverty, where children do not go to bed hungry,” the former civil servant says.

“Life has become so expensive, so hard. We want a better life.”

Onions and inflation

Some in the crowd of a few thousands brandish onions, a household staple and unwitting symbol of Turkey’s eye-watering inflation, which has dropped to 50 percent from 85 percent last year, according to official figures.

Some independent economists believe the real annualised figure could be double the official one.

“I know Turkey’s problems. We all know them and we will solve them,” Kilicdaroglu says.

“We have the knowledge, the experience and the strength. This strength is you!”

Just over a month before the vote, most opinion polls give Kilicdaroglu the lead, although not one large enough to guarantee victory in the first round.

Kilicdaroglu’s path to victory is also complicated by the last-minute entry of Muharrem Ince, CHP’s candidate in the last election in 2018, who is now on course to pick up roughly five percent of the vote.

Erdogan, a veteran campaigner whose popularity has suffered from Turkey’s economic meltdown and the government’s delayed response to a February quake in which more than 50,000 died, is pledging to rebuild a “strong Turkey”.

You will win!

At the foot of the Canakkale stage, Arda Cakirer, a 20-year-old student with an earring and a thin beard, says he is “very moved”.

He will be voting for the first time in May, just like six million other young Turks who have known no leader other than Erdogan.

Cakirer appreciates Kilicdaroglu’s campaign pledge to give up power after serving out one term.

“This is very important,” Cakirer says. “After restoring order in the system, a younger president will be able to take cover.”

Sema Sur, a 40-year-old covered in a headscarf, agrees.

“If we didn’t love him, we wouldn’t have come. We’re soaked, but we love him for the sake of our future, so that hopes can flourish.”

The meeting ends, the rain stops, the umbrellas fold up and a sign brandished above the crowd’s heads looms into view.

“I promise you — you will win!” it assures the candidate.