With President Vladimir Putin’s war heading into its second year, the Polish expansion plan has become jaw dropping in scale. It includes close to 500 HIMARS or equivalent long-range multiple launch rocket systems, just 20 of which allowed Ukraine to inflict serious damage on Moscow’s military machine.

There are also more than 700 new self-propelled heavy artillery pieces planned, over six times as many as in Germany’s arsenal, and three times as many advanced battle tanks as Britain and France can field, combined.

Poland’s wish list is likely to end up being well beyond its means, but it’s also far from unique.

Governments around the world are drawing lessons from Europe’s first high-intensity war since 1945, reassessing everything from ammunition stocks to weapons systems and supply lines, according to current and former defense officials as well as open source records in ten countries and Nato. Some nations are reexamining the very defense doctrines that define what kinds of wars to prepare for.

Ukrainian soldiers call for more Western weapons

The conflict’s effects aren’t limited to Ukraine’s neighbors. China, India, Taiwan and the US are watching closely for implications thousands of miles to the east. So much so that some US officials speak of treating the European and Asian security theaters as interlinked, or potentially at some point as one.

“This is the story of the end of the post-Cold War era, and it ended on February 24, 2022,” said Francois Heisbourg, a veteran French defense analyst and former government adviser, describing a nascent move away from the extreme depletion and restructuring of land forces that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

“All of our armies are going through this, because it’s clear now that none — including the US — have the stockpiles that would be needed to deal with a large, high intensity war,” Heisbourg said.

For many countries nearer to Ukraine, key takeaways include sharply increased defense spending, greater home-grown production capacity and expanded fleets of tanks, artillery and air defense.

Just as critical, according to a study for the UK of lessons learned in Ukraine by the Royal United Services Institute, is to secure the weapons, drones and real time intelligence innovations that have given Ukraine greater precision. That advantage has helped level the battlefield against a much stronger Russian opponent.

So has the speed at which good communications, battlefield apps and an agile command structure have at times allowed Ukraine’s forces to move — an observation that other militaries are taking to heart, according to a Nato official who asked not to be identified speaking about sensitive matters.

Nato defense ministers this week signed off on new political guidance calling on members to invest more in air defense, deep strike capabilities and heavier forces, while underscoring the need for greater investment in digital modernization.

As the defense community gathers for the annual Munich Security Conference, a survey of Group of Seven and selected BRICS countries produced by the organizers highlights a spike in risk perception among populations too — from nuclear war to food shortages — including in China. The MSC’s poll surveyed groups of 1,000 people in 12 countries from Oct. 19 to Nov. 7.

Even Russia-friendly Hungary is bulking up, fearing a more volatile and unpredictable security environment is here to stay. Finland and Sweden abandoned decades of diplomatic caution to apply for Nato membership.

Defense companies that make some of Ukraine’s headlining equipment — not just HIMARS, but the Javelin and NLAW anti-tank systems that made an impact on the early stages of the war, or self-propelled howitzers such as the French Caesar or German PzH 2000 that featured later on — have seen their prospects surge.

A boon for weapon manufacturers

Not surprisingly, weapons designers are watching as the war’s mashup of donated Western-made weapons against Russia’s modernized arsenal creates arguably the largest proving ground for defense industry wares in modern history.

Britain’s BAE Systems Plc, for example, says its bid to produce a replacement for the US Bradley Fighting Vehicle, which the company builds, now includes added armor on top, to defend against modern anti-tank missiles that strike from above where protection is weakest, as well as fixings to mount counter-drone weapons.

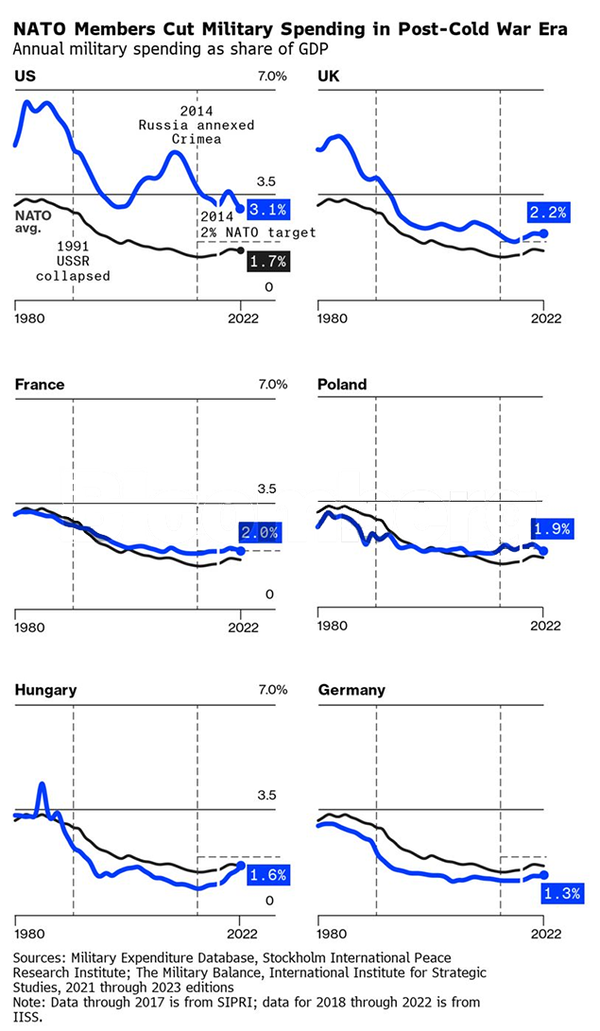

For most Nato member states, the war came as a shock. They had capitalized on a so-called peace dividend after the fall of the Soviet Union, cutting defense budgets, ending conscription and scrapping or selling vast quantities of hardware in the belief a major land war was no longer plausible.

Germany, whose western half alone had thousands of tanks in the 1980s, now has 321, according to the Military Balance, an annual compendium of defense data from the UK’s International Institute for Strategic Studies with the 2023 report published this week. The UK, which allocated 4% of gross domestic product to a 325,000-strong armed force in the mid-1980s, now spends about half that on a combined force of 150,000.

The decline in spending bottomed out in 2014, following Russia’s annexation of Crimea, but the impact of the past year looks to be seismic, even in an era of straitened budgets.

Many European and US officials believe Putin is determined to subordinate Russia’s ex-Soviet neighborhood and will seek to rebuild his army, regardless of the war’s outcome. Estonia’s annual intelligence report, published this month, estimates four years for Russian units depleted in Ukraine to reconstitute on its border.

Poland’s 2023 defense allocation has risen more than two-fold from last year, including 97.4 billion zloty ($22 billion) assigned from the central budget and a further 30 billion to 40 billion zloty to be spent by an off-budget army fund created last year. In total, the government says it will spend 4% of GDP on defense this year — a higher proportion than any Nato state before the war. The three equally nervous Baltic States all have begun Polish-style shopping sprees.

Nato members cut military spending in post-Cold War era

Germany set up a €100 billion ($107 billion) fund to help its budget meet Nato’s 2% of GDP target after years of undershooting and, despite criticism for foot dragging, has been a major contributor of heavy weapons to Ukraine. It is poised to increase its defense budget by as much as €10 billion next year, according to people familiar with the plans.

The boost to funding is reshaping Germany’s defense sector. Rheinmetall AG is investing hundreds of millions of euros in new factories and production lines at home and in nearby countries such as Hungary, aimed at expanding production of tanks and ammunition.

Diehl Defence is ramping up output of its IRIS-T anti-missile system — praised by Ukraine for a near-100% strike rate — which will play a key role in Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s initiative to create a European missile defense shield. Fourteen Nato members plus Finland signed a letter of intent to join the so-called European Sky Shield.

France, too, is looking to restructure its forces for high intensity warfare. The government has announced a new six-year allocation of €400 billion for 2024-2030, up by a third compared to the current six-year spending plan.

Among the more sobering realizations facing the French military is that Russian forces in the eastern Donbas region of Ukraine at times fired as many heavy artillery shells in a week as French manufacturer Nexter says its Caesar 155mm field guns used in 13 years of training and deployments to Afghanistan, Lebanon, Mali and Iraq.

The situation may be even more acute for the UK. According to RUSI, the British military’s entire stock of 155mm artillery shells would have been exhausted in just two days by Russian gunners in the Donbas last summer. Ukraine’s forces would have run out in a week.

An integrated defense review and other strategy papers written as recently as 2021 are already considered out of date and will be revised within weeks, according to a person with knowledge of the conversations.

The Defence Ministry will ask for £10 billion to match inflation and an additional boost in funds to reconstitute a military that was “hollowed out” over decades, the person said. The decision to slash force numbers is, after Ukraine, seen as a strategic error.

The trend to rearm appears to transcend political boundaries. Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orban has said that for him alarm bells rang at a Nato meeting in July, after which he told his defense minister to “radically increase” defense capabilities.

Orban has refused to send weapons to Ukraine and slow-walked energy sanctions against Russia. Even so, the push to rearm shows deep concern about Hungary’s exposure, in what he often calls a “windswept” region of central Europe, fought over by empires across the centuries.

To meet the challenge, Hungary has ordered 45 new Leopard II tanks, 218 Lynx infantry fighting vehicles, an unspecified number of Airbus 225 helicopters and German PzH 2000s, as well as radar and US NASAMS systems to strengthen its air defenses, according to the Defense Ministry.

Many lessons from the war in Ukraine have less to do with hardware than the softer issues of logistics, training and strategy that have no borders.

“The Russians showed how devastating it can be to mismanage logistics,” said Michele Flournoy, a former US Undersecretary of Defense for Policy who chairs the Center for a New American Security in Washington. “It cuts both ways for a Taiwan scenario: 200 miles of ocean is hard for China, but it’s also hard for Taiwan to resupply.”

Japan, along with the US, is concerned that China — which like Russia has been building up its military for more than a decade — may seek to unify with democratically ruled Taiwan by force. It’s a conflict that would be radically different than Ukraine’s, as it would be conducted across the 110 mile (180 km) Taiwan Strait, and could have even more dangerous ramifications, given the scale of China’s economy and resources.

Still, there are takeaways from Ukraine for Taiwan and its allies, including the importance of the training that Kyiv’s forces received in asymmetric warfare during the eight years between Putin’s two attempts to subjugate Russia’s neighbor. “That training, conducted with our allies, was far more effective than we realized,” said Flournoy. “Now we need to figure out how to translate these lessons to Taiwan.”

It’s harder to understand any assessments China is making, because those debates tend to be closely held by the military and would involve deconstructing the battlefield failures of Russia, an economic and strategic partner, in public.

Still, among the publications that provide a window into the thinking of the People’s Liberation Army, one — Naval and Merchant Ships magazine — has addressed the war directly, with a specific interest in how to protect Chinese marines on landing.

Its article on a hypothetical amphibious invasion of Taiwan by China drew on specific lessons from Ukraine, including an incident when Russia said its troops on Snake Island had shot down a Ukrainian fighter jet and 12 rockets. This suggested China should equip its marines with missile defense systems as they land, to protect them until ground forces arrived, according to the article.

“We see folks in the PLA and in China’s defense industry studying the characteristics and effectiveness of various battlefield systems, most of which have applicability to cross-strait operations,” said Joel Wuthnow, a senior research fellow at the DC-based National Defense University’s Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs. “Examples include unmanned aerial vehicles and electronic warfare as used by the Russian military in Ukraine.”

The PLA was already actively exploring how to use drones to help lower level units assess the battlefield more accurately, according to Decker Eveleth, a researcher at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, a Californian research group. Having seen the effectiveness of the Ukrainians in providing individual units with drones to identify and target threats, “that is a lesson that the PLA is interested in studying and utilizing,” he said.

Impact on India’s strategic thinking

India also has potential peer-state conflicts to worry about. While the battlefield conditions would again be very different to the open plains and forests of Ukraine, the war has impacted India’s strategic thinking, according to three senior officials, who asked not to be named because they are not authorized to speak on the matter.

Broad takeaways include the need for greater force integration, a key Russian failure. According to the officials, the government is examining a proposal to integrate drones with mechanized units, and launched a drive to acquire small to miniature surveillance UAVs.

The course of the fighting in Ukraine has pressed home to India its weakness in the longer-range missiles it would need in a potential “non-contact war” along its mountainous border with China, according to the officials. The government has ordered the first batch of 120 new, domestically produced short range ballistic missiles known as Pralay, which are similar to Russia’s Iskander.

India has also ordered more shoulder-held anti-aircraft missiles, known as MANPADS, for use at the border with China. The MANPADS, including US Stinger missiles that Ukraine has dispersed widely among its troops, have proved a key element in its effort to deny Russia air dominance.

Yet perhaps the most important conclusion drawn in New Delhi is that it can no longer rely so heavily on Moscow for arms. Russia has had to dedicate production capacity to the war effort, causing supplies of spare parts to customers abroad to dry up.

India is looking to partner more with the US and France in particular to buy weapons, the officials said. It has also earmarked two thirds of the defense procurement budget for domestic producers — often in joint ventures with foreign arms makers — up 7 percentage points from the 2022-2023 fiscal year.

“Sustenance of Russian origin equipment is an issue,” India’s Army Chief Manoj Pande told reporters last month, adding the military was “looking at alternate sources of supplies.”

Learning the right lessons

While the war in Ukraine does mark a huge change, there are risks in rushing to conclusions with the outcome still so unclear, according to Dara Massicot, a senior researcher on military affairs and Russia at the Rand Corporation, a California-based think tank.

Most Russian tanks, for example, were not destroyed by Javelins or NLAWs as widely thought, but by directed artillery. Russia’s armed prowess was first exaggerated by observers and then dismissed, together with the quality of its weapons.

Much could change should Russia learn from mistakes and deploy its air force more effectively. “We just have to be really careful about the lessons we learn from this,” said Massicot.

Poland, for one, isn’t waiting.

Defense Minister Mariusz Błaszczak said last year that Poland will create two new army divisions to boost defenses in central and eastern Poland, a project requiring about 20,000 new troops. The government also said it jettisoned long-standing invasion-response plans that had been based on a deep defense strategy, backstopped by the Vistula River. The Vistula runs through Warsaw, splitting the nation in two.

The Pentagon’s Feb. 7 approval to sell Poland 18 HIMARS and associated munitions in a roughly $10 billion package was just a fraction of Poland’s original request for 486 of the systems — almost as many as Lockheed Martin Corp has ever made.

The US company said last year it will increase production to 96 HIMARS per year. Even so, such a large order would take years to process and has yet to be approved by Washington.

Rather than stand in line, Poland has asked for 288 units of South Korea’s equivalent to the US M270, the HIMARS’ heavier twin that carries twice the number of rocket launchers. So far it has signed up for 218 of the K249 Chunmoo multiple launch rocket systems, which are compatible with HIMARS ammunition. The first 18 are expected this year.

As determined as Warsaw is to rebuild the nation’s defenses, there is wide skepticism as to whether the country can sustain it, an issue likely to stress a number of other Nato treasuries as they juggle the growing demands of both health care and defense on aging populations.

For one thing, last year’s Homeland Defense Act envisages boosting Polish troop numbers to 250,000 from 114,000 in 12 years. That implies a net addition of more than 11,000 soldiers a year, at a time when the armed forces are struggling to retain existing soldiers.

Adding hundreds of HIMARS or Chunmoos would require huge resources, on top of already stratospheric purchase costs, including several thousand well-trained personnel to operate, supply and maintain them. The systems would need warehousing for thousands of rockets the size of kayaks.

With close to 1,400 new main battle tanks also envisaged, including 366 US Abrams ordered just before and after the start of the war and 1,000 South Korean K2 Panthers (with most of the latter to be built in Poland), the maintenance and logistics chains to support them will be vast.

“While the general direction seems to be correct, when looking at the numbers of new equipment ordered I am not sure if anyone conducted a thorough analysis on the locations where the army should store it, and who will later operate it and maintain it,” said Tomasz Drewniak, a former general and Inspector of the Air Forces.

Just arming the 96 Apache helicopters on Poland’s shopping list for flight, with each carrying 16 Hellfire rockets at well over $100,000 a piece including spares and maintenance, would cost at least $150 million.

“The cost of new equipment accounts for only 25% to 30% of the entire budget needed to maintain troops,” said Drewniak. Recalling the dire state of the Polish armed forces after the collapse of Communism, he added: “I used to serve in an army of 300,000 that had no resources for anything, not even for fuel or meals.”