The group, whose members are between the ages of 5 and 20, found a home with the Capital Circus of Budapest after leaving their circus schools and lives behind in the cities of Kharkiv and Kyiv in March 2022.

Trainer Svetlana Momot, who fled Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second-largest city, with an initial group of 12 of her students last year, watched and reflected Monday as some of the young circus artists swung from suspended rings, dangled from aerial silks and rehearsed acrobatic stunts in one of the Budapest circus’ training halls.

Momot said that in the past year, the performers had to learn to live, cook, clean and study together in close quarters. But her goal from the beginning was to ensure that, despite being uprooted from their homes, their intensive daily training would not be interrupted.

“When they’re busy (with training), they don’t have time to think about the bad things. It distracts them,” Momot said. “What I see is that we live as one family and as a creative team. … I think it hasn’t affected their training, and I try to keep them in the form they were in Ukraine.”

After Russia invaded Ukraine, the Budapest circus and a Hungarian school for acrobats extended their solidarity to the Ukrainian performers, offering them accommodation, food and the ability to continue their training, Capital Circus of Budapest director Peter Fekete said.

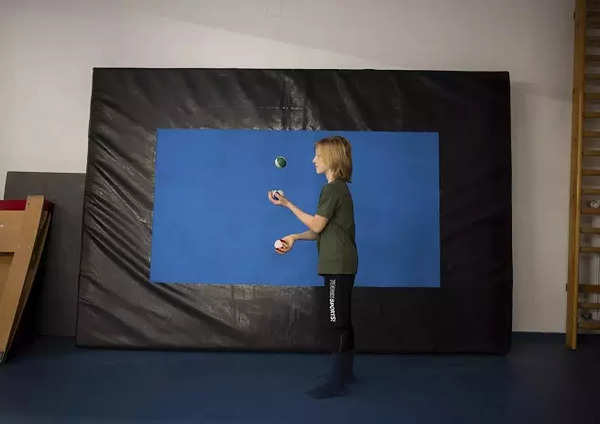

A Ukrainian refugee circus student practicing juggling in a training room in Budapest (AP photo)

“We have to realize that all people need a purpose in life. Even an 8-year-old child can ask the questions, ‘Why am I alive, what is my purpose in the world?’” Fekete said.

“If we provide an opportunity to train, and if we set goals that we want to achieve through opportunities to perform, then in their everyday lives they won’t be focused only on the difficult situation they are in, but artistic performance can fill their lives to some degree,” he said.

Anna Lysytska, a 14-year-old acrobat, said it had been difficult at first to adapt to life in Hungary after fleeing her home in Kharkiv. But staying focused on her training, she said, had helped ease the transition.

“At first it was hard, but then we got used to it a little and started to go to our training sessions,” she said. “We set up a routine and then started studying at a Hungarian school. We love it here.”

A group of young Ukrainian refugee circus students practicing in a training room in Budapest (AP photo)

Lysytska’s twin sister, Mariia, said what she liked most about Hungary at first was that “there were no explosions,” but that she had since formed friendships that made it easier to be far from home.

“When we came to this school, we became friends (with the Hungarians) right away and started communicating with them, so I have positive feelings about it,” Mariia said.

While some of the performers plan to eventually join family members who have settled in countries like Germany and Slovakia, almost all of them want to return to Ukraine whenever the war ends, Momot said.

“We were all in the same situation where we had no other option but to leave people behind in Ukraine. Our families are broken,” she said.

Still, as Russia tries to ramp up an offensive in eastern Ukraine and to bolster its hold on other parts of the country, it remains unclear when the performers can return safely to their homes. Until then, their futures, and the question of where home is, remain up in the air.

The Ukrainian troupe recently returned from a competition in Monte Carlo, Fekete said, where two of the performers brought home gold and silver medals.

“When I hugged one of the little girls at the airport and I said we were going home, I corrected myself and said, ‘Well, home to me.’ She stopped me and said, ‘It’s home for me, too,’” he said.