WASHINGTON: Few expect Chinese President Xi Jinping‘s diplomacy to yield breakthroughs on the Ukraine war. But in Washington, there are fears Beijing may succeed elsewhere — in winning credibility on the world stage.

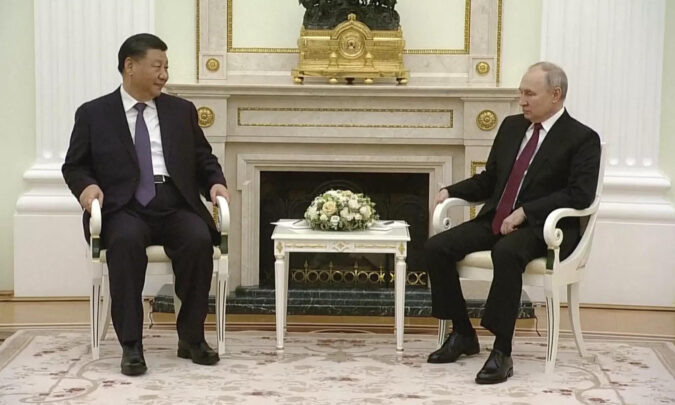

Xi pushed forward positions on Ukraine during two days of talks in Moscow, a week after China announced the restoration of ties between Iran and Saudi Arabia — rivals in a region where the United States for decades has been the main diplomatic powerbroker.

The United States has been skeptical of China’s diplomatic offensive, believing its proposed ceasefire would only provide time for Russia to regroup forces that Ukrainians have been succeeding in pushing back for more than a year.

“The world should not be fooled by any tactical move by Russia — supported by China or any other country — to freeze the war on its own terms,” Secretary of State Antony Blinken said.

But US officials and experts say that China’s diplomacy is not so much about ending the war as an attempt to change the narrative.

Xi “would like to be seen and be taken seriously as a peacemaker,” said Robert Daly, director of the Wilson Center’s Kissinger Institute on China.

“He’s more interested in that right now than actually doing specific things to attain peace in Ukraine. This is mostly about messaging.”

The United States has increasingly found success in persuading Western allies to see China as a global threat — a perception that has grown in Europe after US assertions that Beijing is considering supplying weapons to Russia.

Daly doubted China would provide major military support unless it sees a serious threat to President Vladimir Putin, Xi’s biggest ally in confronting the United States.

But Daly said Xi casting himself as a mediator could help at the margins in Europe — and especially in developing nations which share little of the US enthusiasm for preserving an “international rules-based order.”

Xi “doesn’t actually have to move the needle on peace or a ceasefire in Ukraine. All he has to do is profess interest in peace and, somewhat contradictorily, in sovereignty and respecting others’ territorial integrity and he gets what he needs.”

The United States for years has called on China to assume more global responsibilities commensurate with its aspirations. Blinken allowed that Iran-Saudi reconciliation was a “good thing” even if brokered by China, which relies on oil imports from the rivals.

But China has entered only into selective spots. Iran and Saudi Arabia had already been looking at patching up, and any mediation would have been nearly impossible by the United States which has no diplomatic relations with Iran’s clerical rulers.

James Ryan, director of the Middle East program at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, said that China’s interest in the two countries was “purely economic.”

“China is not going to be providing security guarantees to this deal,” he said.

Yun Sun, director of the China program at the Stimson Center, said that the Iran-Saudi Arabia deal has “made a lot of people in the US uncomfortable.”

“The Chinese were just at the right time and the right place with the right relationships,” she said.

“They exploited the opportunity to be a mediator. In fact, they cannot mediate — there’s nothing they can offer.”

Sun said that China at least was stepping back from “wolf warrior” diplomacy — its shift in the past decade to a shrill, coercive style of dealing with other countries.

“But if the question is have the Chinese been able to come up with a new alternative world order, I don’t think so.”

Evan Feigenbaum, a former US official now at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, wrote in an essay that China has already won support for its efforts in parts of the world less invested in the Ukraine war, such as Brazil.

China’s diplomacy can only help, if not by much, in Europe — and there is no thought of winning over the United States, he said.

“Beijing will have already concluded that Washington will dismiss any Chinese diplomatic activity as performative — a kind of Peking opera,” he wrote.

“But the Americans are not China’s audience, so Beijing likely does not much care what Washington thinks.”

Xi pushed forward positions on Ukraine during two days of talks in Moscow, a week after China announced the restoration of ties between Iran and Saudi Arabia — rivals in a region where the United States for decades has been the main diplomatic powerbroker.

The United States has been skeptical of China’s diplomatic offensive, believing its proposed ceasefire would only provide time for Russia to regroup forces that Ukrainians have been succeeding in pushing back for more than a year.

“The world should not be fooled by any tactical move by Russia — supported by China or any other country — to freeze the war on its own terms,” Secretary of State Antony Blinken said.

But US officials and experts say that China’s diplomacy is not so much about ending the war as an attempt to change the narrative.

Xi “would like to be seen and be taken seriously as a peacemaker,” said Robert Daly, director of the Wilson Center’s Kissinger Institute on China.

“He’s more interested in that right now than actually doing specific things to attain peace in Ukraine. This is mostly about messaging.”

The United States has increasingly found success in persuading Western allies to see China as a global threat — a perception that has grown in Europe after US assertions that Beijing is considering supplying weapons to Russia.

Daly doubted China would provide major military support unless it sees a serious threat to President Vladimir Putin, Xi’s biggest ally in confronting the United States.

But Daly said Xi casting himself as a mediator could help at the margins in Europe — and especially in developing nations which share little of the US enthusiasm for preserving an “international rules-based order.”

Xi “doesn’t actually have to move the needle on peace or a ceasefire in Ukraine. All he has to do is profess interest in peace and, somewhat contradictorily, in sovereignty and respecting others’ territorial integrity and he gets what he needs.”

The United States for years has called on China to assume more global responsibilities commensurate with its aspirations. Blinken allowed that Iran-Saudi reconciliation was a “good thing” even if brokered by China, which relies on oil imports from the rivals.

But China has entered only into selective spots. Iran and Saudi Arabia had already been looking at patching up, and any mediation would have been nearly impossible by the United States which has no diplomatic relations with Iran’s clerical rulers.

James Ryan, director of the Middle East program at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, said that China’s interest in the two countries was “purely economic.”

“China is not going to be providing security guarantees to this deal,” he said.

Yun Sun, director of the China program at the Stimson Center, said that the Iran-Saudi Arabia deal has “made a lot of people in the US uncomfortable.”

“The Chinese were just at the right time and the right place with the right relationships,” she said.

“They exploited the opportunity to be a mediator. In fact, they cannot mediate — there’s nothing they can offer.”

Sun said that China at least was stepping back from “wolf warrior” diplomacy — its shift in the past decade to a shrill, coercive style of dealing with other countries.

“But if the question is have the Chinese been able to come up with a new alternative world order, I don’t think so.”

Evan Feigenbaum, a former US official now at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, wrote in an essay that China has already won support for its efforts in parts of the world less invested in the Ukraine war, such as Brazil.

China’s diplomacy can only help, if not by much, in Europe — and there is no thought of winning over the United States, he said.

“Beijing will have already concluded that Washington will dismiss any Chinese diplomatic activity as performative — a kind of Peking opera,” he wrote.

“But the Americans are not China’s audience, so Beijing likely does not much care what Washington thinks.”