Nudge growth?

The one line answer to this question is: protecting macroeconomic stability and focusing on quality of spending. The other way to put this is that the Budget is not obsessed with giving an immediate (and artificial) boost to economic growth.

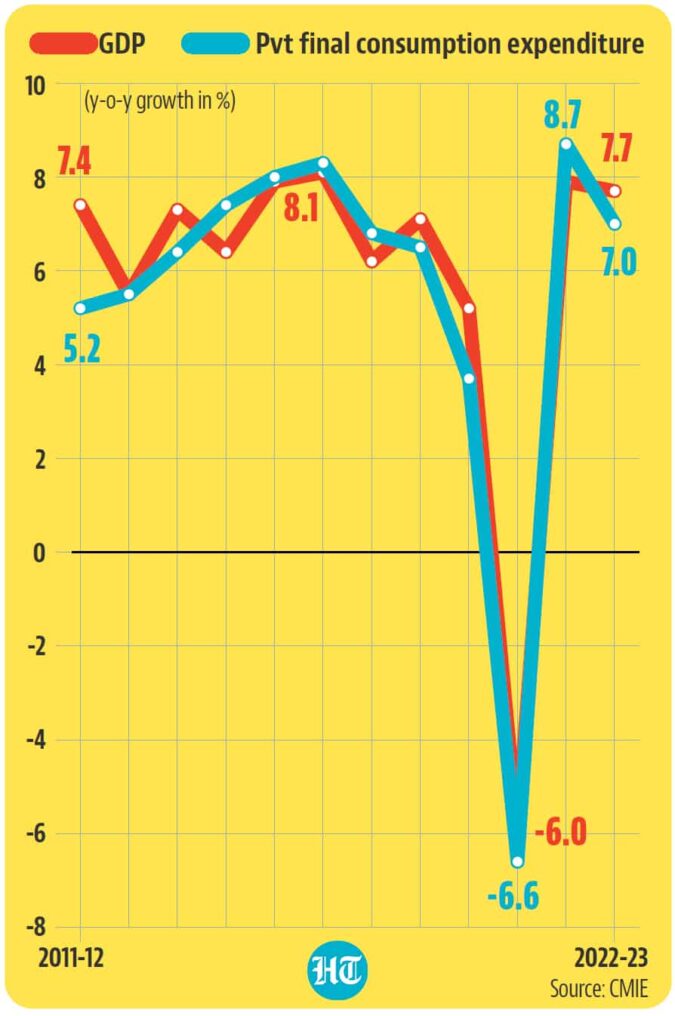

The context to this answer is that Indian economy is anyway expected to slow down in 2023-24 compared to 2022-23. Real GDP growth in 2022-23 is expected to be 7% and the Economic Survey has projected a baseline GDP growth of 6.5% for 2023-24. The upside in this growth moderation story is that India will continue to be the fastest-growing major economy in the world and it will be performing in line with its medium-term potential growth rate (IMF estimate) of 6%. Perhaps this is what convinced the government that the best way to boost Indian economy’s long-term prospects (its policymaking horizon is 2047 when India completes 100 years of independence) is to crowd in private investment by pump priming public investment.

A research note by HSBC economists Pranjul Bhandari and Aayushi Chaudhary points that revenue-to-capex-expenditure ratio has fallen from 6.5 in the pre-pandemic years to a budgeted 3.5 in 2023-24. To be sure, the strategy, as of now, has not been as successful as the government expected it to be. The Economic Survey dropped a hint on this front when it emphasised that “private capex soon needs to take up the leadership role to put job creation on [the] fast track”.

Almost all economists agree that India cannot achieve a sustained high growth trajectory without a manufacturing revolution. The flagship Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme to promote manufacturing has seen a gradual expansion, both in terms of allocation and sectors included. And this year’s Budget has tended to a common criticism by many economists about correcting the inverted duty structure to help the cause of manufacturing in India. It has brought down customs duties on key manufacturing inputs such as mobile phones and TV components. It is clear that the budgetary announcements and the government’s overall policy direction are geared towards its efforts to take over some part of China’s role in global supply chains.

Where does macroeconomic stability fit in the growth narrative of the Budget? The global economy continues to face turbulent weather and it is bound to generate headwinds for the export engine of growth. India’s economic policy has been extremely cautious in this milieu. The Reserve Bank of India has aggressively hiked rates to boost its inflation targeting credentials and the Budget has reiterated its commitment to fiscal consolidation. By doing this, the government expects domestic headwinds (to growth) of such actions to be compensated by tail winds from a more favourable outlook by foreign capital, both of the greenfield (foreign direct investment) and financial (foreign portfolio investment) variety. This, the government is perhaps hoping, will help in replenishing India’s foreign exchange reserves, maintaining the relative premium Indian equity markets enjoy vis-à-vis peers – the wealth effects of an adverse movement here can be significant now – and convince large investors that India’s long-term macroeconomic stability is intact under the current regime.

Is there a weak link in this growth strategy? One could emerge if the impact of schemes such as PLIs is not significant enough to compensate for the loss in economic momentum from the informal sector of economy which will put a squeeze on earnings for a huge majority of workers. Add to this the fact that some of the consumption demand in 2022-23 was exhaustion of pent-up demand and the growth narrative of the Budget could fall short of the required ballast from animal spirits of private capital which the government anticipate.

Spur consumption?

The Budget has pinned its hopes on boosting personal disposable incomes rather than personal incomes by offering relief to the lowest and highest income earners in the income tax bracket. This policy, as is the case for most economic policy objectives of the current government, has been in the making for the past few years.

Let us cut through the economic jargon of personal income versus personal disposable income. A lot of saving decisions in India, especially by income tax payees, have been the result of a nudge from the income tax regime, which has traditionally allowed deduction of such payments from the taxable income thereby bringing down tax liability. Such payments include premium for life insurance policies, most of which in reality are small savings plans and many other heads such as house rent deduction or interest payments on housing loans. Tax saving is, in fact, a major driver behind low-ticket house purchases in India.

When the government introduced the new tax regime in 2020, it offered significantly lower tax rates to income tax payers, provided they were willing to let go of the exemptions offered. This year’s Budget has further lowered the tax rates in the new tax regime and announced that it will be the default regime for income tax payments. The only economic logic of such a policy will be that the government hopes that the amount not paid in taxes will now be spent by the taxpayers, thereby, giving a boost to private consumption.

By bringing down the marginal tax rate on the super-rich, the government is perhaps hoping to achieve two objectives. One, slow down the (not insignificant) exodus of the high net worth individuals to tax havens or low tax countries. And two, deploy the prime minister’s political capital to nudge the rich to spend more in the domestic economy. The Prime Minister’s appeals asking domestic tourists to spend on local artisanal products and the Budget’s reiteration of this appeal as well as announcing tied capital grants to promote state-level artisanal malls are moves in this direction.

Will this plan work? The long-term impact of dropping the nudge towards forced savings to save taxes will not be insignificant. The positive impact on consumption spending could increase further if the government eventually drops the old-tax regime completely.

Is there a problem with this kind of a strategy to boost consumption? At one level, there is. Almost 40% of India’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) basket comprises food items. This is basically a reflection of the fact that the average Indian household is still struggling to make ends meet and anyway spends most of its income. Only income growth can increase the consumption of this segment.

And at another level, there isn’t. As consumer products marketers will vouch, much of consumption is driven by the middle- and upper-classes.

And to be sure, the government’s answer to the criticism of the first part is that its formalisation push will increase incomes as well.

Mange the fisc?

Headline numbers are impressive, to say the least. The Budget promises a 50 basis point – one basis point is one hundredth of a percentage point – reduction in fiscal deficit in a year when nominal GDP growth is expected to slow down by almost five percentage points. That this will be achieved without increasing tax rates or cutting total expenditure is even more promising.

Has the Budget done some magic here? Not really, if one looks at the fact that the fiscal consolidation in this year’s Budget is only a return to business as usual fiscal scenario. A gross fiscal deficit of 5.9% is still too high if one excludes the post-pandemic period and a complete return to the fiscal glide path continues to be a work in progress.

The real question to ask, as far as fiscal management is concerned, is what has changed in a gradual return to business as usual scenario?

The answer is straightforward. A rollback from government’s revenue expenditure commitments in the post-pandemic period, even as capital spending continues to receive a boost. A large part of revenue spending is a given. It is spent on things such as salaries and interest payments. In absolute terms it will still grow by 1.25% between 2022-23 (Revised Estimate) and 2023-24 (Budget Estimates).

The cutback that has happened on the revenue expenditure front is what can be described as its counter-cyclical component. Allocations for subsidies and MGNREGS spending are the biggest examples.

The other key piece of the puzzle to the fiscal maths is a higher tax buoyancy estimate in 2023-24 (BE) compared to 2022-23 (RE). These numbers are 0.99 and 0.8 respectively. The assumption is on the bullish side, given the fact that a lot of earning in the formal services sector is tied to global business environment, which is bound to go southwards next year. However, what could still bail out absolute tax collection numbers despite actual tax buoyancy ending up lower is the fact that the Budget has made a relatively conservative nominal GDP growth estimate of 10.5%.

To be sure, there is more to the fiscal deficit than a balance between government’s taxes and spending. Other heads of government receipts include dividends, disinvestment receipts and market borrowings. The government has factored in higher dividends from RBI, higher disinvestment receipts and higher mobilisation through small savings schemes to compensate for what analysts see as a lower than expected increase in market borrowings which is expected to increase from ₹11.95 lakh crore to ₹12.3 lakh crore.

The other cushion to the fiscal calculations could of course come from the budgeted capital spending of ₹10 lakh crore not being spent entirely, not because of intent but logistical difficulties in making such spending. A lot of such spending is contingent on things such as land acquisition and environmental clearances.

The fact that the RE numbers for capital spending are lower than the BE numbers for 2022-23 lends support to this argument.

To sum up the key takeaway from the fiscal claims made in the Budget is that the government is willing to pursue fiscal consolidation, even if it entails a reduction in revenue spending a year before the 2024 general elections. The numbers might change slightly, but this direction is unlikely to change until the next Budget.

Help build infrastructure?

All roads lead to 2047 in India. This year’s Budget has seen a massive hike in capital spending which has crossed the ₹10 lakh crore mark for the first time.The increase in capital spending between 2022-23 RE (revised estimate) and 2023-24 BE (Budget estimate) is a massive 37%, driving almost the entire increase in total spending which has grown by 7.5%.

Boosting India’s physical connectivity is the key area as far as the capex growth is concerned. The Budget talks about 100 transport infrastructure projects to boost end to end connectivity for ports, coal, steel and fertiliser sectors. Capital outlay for railways has been increased by almost ₹1 lakh crore. The Budget also talks about reviving fifty additional airports, heliports, water aerodromes and advance landing grounds to boost regional air connectivity.

The Centre’s obsession with capital spending is not just in terms of its own budgetary allocations. The Budget also shows an intent to direct the nature of capital spending by states. While the Budget has increased the allocation for 50-year interest-free loans to states for infrastructure spending to ₹1.3 lakh crore, the incentives have been tweaked to suit the Centre’s priority areas, which will include things such as setting up “Unity Malls” to tap into tourist spending and improving urban sanitation infrastructure to eradicate manual scavenging.

To be sure, the government also hopes to tap private funds to aid its infrastructure push via an increase in capital spending. “The newly established Infrastructure Finance Secretariat will assist all stakeholders for more private investment in infrastructure, including railways, roads, urban infrastructure and power, which are predominantly dependent on public resources,” the finance minister said in her Budget speech. As a follow up to this ambition, she mentioned an expert committee reviewing the “The Harmonized Master List of Infrastructure” to recommend “the classification and financing framework suitable for Amrit Kaal”.

This is a critical area given the ambitious private sector infrastructure spending targets in the run-up to 2047 (the government refers to period between now and then as Amrit Kaal). Infrastructure projects are by definition long-term in nature and commercial banks are not the best entities to provide such borrowing. Stress in infrastructure lending was a major reason behind the rise in non-performing assets of the banking sector in the last decade. It remains to be seen what the exact instrument for financing such projects is going to be.

While the Centre’s infrastructural ambitions are laudable and critical to boosting India’s long-term growth prospects, especially in manufacturing, this is one area where an aggressive approach can also inflict collateral damage. A lot of infrastructure projects are located in fragile environmental ecosystems and pushing for such projects without necessary caution and moderation, if need be, has the potential to create irreversible environmental damage. The recent crisis in Joshimath, the Uttarakhand hill town where hundreds of houses have developed cracks and have become unlivable, is one example.

To be sure, this is not the first government which is prioritising development over environment. However, with the worsening climate crisis and pressure on fragile ecosystems higher than it has ever been, the room for error is much lower than what past governments enjoyed.

This Republic Day, unlock premium articles at 74% discount

Enjoy Unlimited Digital Access with HT Premium