Henrik Utvik: If carbon capture fails, it’s actually hugely bad news for society because a lot of the companies that make the basic building blocks that we take for granted in a modern society won’t be able to operate at the same cost level without it.

Shana Ting Lipton: That’s Henrik Utvik. And today we hear the story of how his startup, Aqualung, is setting out to commercially scale its patented carbon capture and storage technology [known as CCS] to support decarbonization in heavy industry and transport. I’m your host, Shana Ting Lipton, with PwC, and this is Voices in Tech, from our management publication, strategy+business, bringing you stories from the intersection of technological acceleration and human innovation.

In 1996, Norway launched the world’s first large-scale commercial carbon capture and storage project, demonstrating that CO2 could be removed from a natural gas production facility and injected into a sandstone formation, where it was stored under the North Sea. It was described as Norway’s moon landing. It’s often touted as a CCS success story and continues to capture and store 1 million metric tons of CO2 from natural gas annually. But to put it into perspective, some scientists say we need to capture at least 5 billion metric tons of CO2 annually by 2050 [to achieve the Paris Agreement’s target of net-zero GHG emissions by 2050].

Can CCS move the needle on this? It’s been hailed by some as one of the most promising tools for industrial decarbonization. But critics cite the enormous cost of implementing it and question whether it can be scaled quickly enough to meet today’s urgent carbon-reduction demands.

Here’s Jürgen Peterseim, Director, Sustainability Services, PwC Germany.

Jürgen Peterseim: Carbon capture can have quite a bit of muscle in making a dent in the global emission curves. But we have to look at this sort of from a twofold angle: one is the technical; one is economic. From a technical one, yes, it can cover many industries, energy-intensive industries. It can cover the power sector, the oil and gas sector.

It’s important to mention, though, that with fossil fuels being finite, it’s a transition technology—a transition technology, though, with a relatively long lifespan. If you start building such a facility and operate it, it’s going to be in operation for 30 to 40 years.

If you look at the economic angle, then CCS is not a silver bullet, right, because you’re competing within each sector with different technologies. And that means carbon capture will play a role in some industries, while in other industries it’s going to be more economical to use other alternatives, like renewable electricity or the electrification of processes.

Lipton: CCS has been around since the ’70s, when it was used for a different purpose: by the oil and gas industry, to squeeze every last drop of fossil fuel out of aging wells by injecting them with captured CO2. And it’s fair to say it’s still tainted by that association, with its opponents arguing that it gives oil and gas a “Hail Mary” to continue operations that should be phased out. Aqualung chief technology officer and cofounder Henrik Utvik.

Utvik: Carbon capture has always, as a solution, suffered a little bit from being seen as an enabler of oil companies, but all kinds of industrial companies—like, for instance, cement plants—they also have large process emissions that come from the actual industrial manufacturing process itself they can’t really take care of with renewables. The big challenge with applying renewable energy, for instance, to large-scale industry is that the industrial plant has to produce something all the time, and the energy has to be constantly available. Otherwise, the cost really goes really, really high up, since a lot of the economics are based on the utilization of the plant itself. These industries are called hard-to-abate because they cannot use the intermittent energy supply really, such as renewables. For instance, the wind doesn’t always blow, and the sun doesn’t always shine.

Lipton: Aqualung Carbon Capture is hoping to accelerate commercialization of CCS in hard-to-abate industries like cement and lime production, and in transport, through its adaptation to current CCS technology.

Utvik: There are a few main technology options for doing CCS. The most normal ones are these spray chemicals. You basically take a chemical that likes CO2, with water, and then you build a big, big spray tower around the exhaust, and you spray in this chemical, and then the CO2 kind of falls down. Now, this is economically sustainable for very large-scale power plants, but because of the cost of building out these spray towers, it is not viable for industries such as cement and steel. They don’t have the real estate, basically, to install them. In some of these spray chemical projects, there was additional cost because they had to buy huge additional pieces of land next to the existing site, and rebuild large parts of the existing site as well.

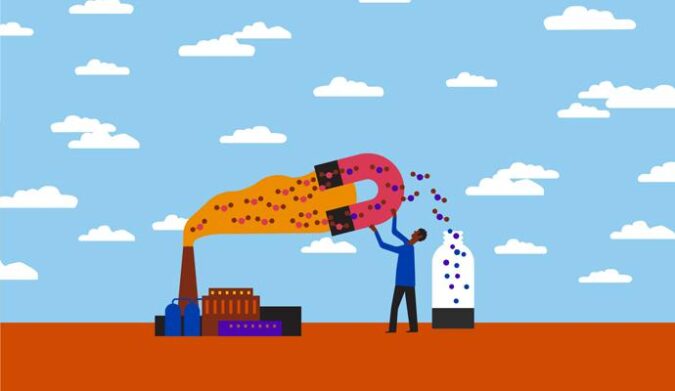

Lipton: Aqualung thinks it has an economical solution. The chemical spray method, which Utvik describes, is the most mature of the CCS technologies and was used at Norway’s first carbon capture facility in the ’90s. Aqualung employs a different process, where CO2 is effectively filtered out on-site through scalable porous membranes. Aqualung took this membrane technology and made it more effective by applying an additional element that is said to make the system altogether more scalable, more compact, and less costly.

Utvik: Basically, membrane technology are these light, cylindrical filters, and you put them in a metal box and you stack multiple together, and then you transport them to the site, and you just build them up like a Lego house.

Traditional membrane separation is based on pressurizing the gas. Due to this huge volume of the gas in an industrial setting, these membrane processes are quite expensive, particularly if you compare them to the current price of CO2 [offsets]. We are taking these conventional membranes and applying what we call our special sauce, which is a type of coating that acts as CO2 magnets, and then scale that up to be ready for large-scale industrial applications. And the CO2 magnets substantially reduce energy costs because they decouple the CO2 capture from pressure, and, then, of course, because the whole technology in membrane is very, very compact, it substantially reduces complexity and cost of installation as well.

Lipton: Their special sauce is what you might call an overnight success that was 20 years in the making. It’s part of the startup’s origin story, that takes us back to Trondheim, a fjord-side city in central Norway.

Utvik: The technology originates from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology [NTNU], which is the world leader in this kind of niche field of membrane separation, and particularly they have been researching various ways of doing carbon capture for many decades. By 2020, they had optimized this recipe to make a membrane into kind of a CO2 magnet and were ready to commercialize. At the same time, myself and two of my business partners had been involved in a few carbon capture projects, utilizing existing technology. The projects had actually a very, very hard time in getting off the ground. We realized that the big value in carbon capture really was in trying to take a more early-stage, promising technology to market. We contacted NTNU, and just as they were in the process of trying to license and patent this technology, we felt that we had the right set of skills—both from their research domain knowledge and [from] our knowledge in terms of developing and scaling up technology, finding the right partners, finding the right customers at the right time, and raising money.

Lipton: With business interest in CCS rising, in 2021, Utvik cofounded Aqualung in Oslo, where its research arm is based. Funding came from a mix of European government grants and, in 2022, a [US]$10 million equity investment from strategic partners.

Utvik: We raised some seed funding from a consortium of investors, and then we attracted a set of partners that were in kind of the core target markets—for instance, in lime, in the refineries, and in some other type of industries, companies that were potential end-users—and they have been our main investors and backers. We also raised the capital from a big CO2 pipeline company. In addition, we received grants from the Norwegian Research Council and also Horizon Europe, which is a big EU-funded grant mechanism. The EU have always been at the forefront of creating mechanisms and incentives to support decarbonization and, to some extent, also carbon capture. The issue is that there is, so far, not the great availability of cost-effective sequestration of the CO2 available in Europe. The US is much more attractive because of its energy price. [It] makes carbon capture in general more viable and also, obviously, the availability and the development now of CO2 pipelines and geology for sequestering CO2 and utilizing CO2 as well.

Lipton: The US, the world’s number two CO2 emitter, has been paving the way for commercializing CCS technologies through decades of investment, through projects as well as policies. PwC’s fourth annual State of Climate Tech report cites the grants, incentives, and other funding options available under policies such as the US Inflation Reduction Act as one reason climate tech investments in North America have moved towards tackling industrial emissions. Jürgen Peterseim.

Peterseim: Regulation is important to get CCS off the ground, and there are different approaches across the world. In the US, for example, we see a much more proactive approach to CCS. We see projects being developed. We see pilot plants operational. There’s certainly regulatory support. In the European Union, it’s a bit more complicated. I mean, until recently, we couldn’t even transport CO2 across borders. So that’s being changed now. At the end of the day, we need to transport CO2 from energy-intensive industries across borders, towards the storage facilities.

Utvik: The real frontier of carbon capture, or where it’s going to be deployed at scale, is really the US. Aqualung has always been very, very US focused. I mean one of the original founders of Aqualung had been very involved in the energy landscape in the US for a long time. One of our focus areas from the beginning was to build out the relationship with the companies that were operating pipelines and developing sequestration spots in the US, and tune our technology to their needs—particularly in Texas, Arkansas, Louisiana.

Lipton: The startup’s CEO is based in the US, where he can continue building those industry relationships. Utvik, who is in London with the company’s scale-up team of engineers and test rig, is focused on plant engineering and managing pilots.

Utvik: Our approach has always been to pilot out in the industry and with the end-users that we are going to work towards at scale. We have four pilots on four different sites. The lime pilot in Sweden. We have a pilot for natural gas boilers and turbines in the southern US, where you could eventually take CO2 out from industrial processes and into lithium production. And then we have a pilot for waste to energy in Germany. And we also have a test rig that can go on multiple flue gases, which is currently situated in London.

Lipton: This sort of innovation seems to line up with one of the recommendations that emerged from the final text of COP28 in 2023. It called on nations to accelerate abatement and removal technologies—specifically citing carbon capture and storage.

Peterseim: Carbon capture technologies would be one piece of the decarbonization puzzle. And it’s going to be a relevant piece for sectors such as cement or chemicals because in these sectors we cannot abate 100% without carbon capture.

Utvik: If carbon capture fails, it’s actually hugely bad news for society because a lot of the companies that make the basic building blocks that we take for granted in a modern society won’t be able to operate at the same cost level without it.

Lipton: Even after decades of research, there are still multiple challenges to overcome to turn this into a viable commercial solution, not the least of which is the urgency of today’s climate challenges and the timelines for commercializing CCS. Case in point: Aqualung’s target for being production scale–ready by 2026 or 2027. Henrik Utvik.

Utvik: Customers come and talk to us, and we say that we can be ready to supply them maybe in 2027, and they say, “Already in 2027?” This sounds like long timelines, but actually in the context of the industry of carbon capture, it’s actually very, very short. Because of the complexity of these projects, they need to put the full value chain together. So, Aqualung was founded on the idea that you need cross-collaboration between many different disciplines in order to make a success. And we have applied that thinking also to our partnerships and to our further development—commercial development—of the company.

Peterseim: For carbon capture to make a dent in the global emission curve, we’ll have to look at the entire ecosystem—meaning the industries (cement, chemical, the transport sector) bringing the CO2 to the final destination; the finance sector, providing the required investment into this large-scale infrastructure; and the public sector, to provide the regulation that these become sort of bankable investments. The ecosystem is increasingly complex, but no industry can solve this alone, so they will have to collaborate to meet the Paris Agreement, with carbon capture playing a role in selected industries.

Lipton: Thanks for listening, and stay tuned for more episodes of Voices in Tech, brought to you by PwC’s strategy+business.