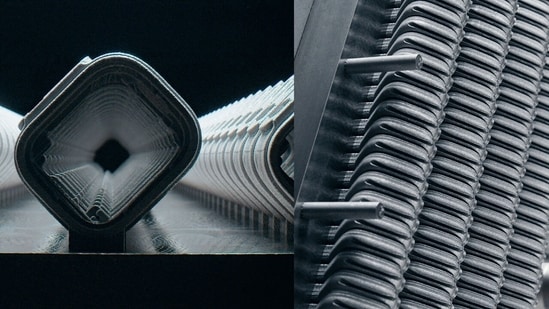

This year, Apple made a big leap that will have a two-pronged impact, that is not just with how its product lines are defined, but a manufacturing breakthrough which could redefine how the tech industry approaches sustainable production. The Apple Watch Ultra 3 and the titanium Apple Watch Series 11 become the first tech products that are 3D printed with 100% recycled aerospace-grade titanium powder. That isn’t the only product line adopting the newer manufacturing methodology — the iPhone Air’s USB-C port has a titanium enclosure 3D-printed with recycled titanium powder, which allowed it to be thinner than usual. Apple executives, in a conversation with HT, describe this as a “big breakthrough” with what was previously a high-in-the-sky challenge.

“We hope others come along with us, change the system and change the approach,” says Sarah Chandler, vice president of Environment and Supply Chain Innovation. For Chandler, her focus is on improving manufacturing processes, which she said is all about figuring out how to build products that are good for people and good for the planet. Kate Bergeron, Vice President of Hardware Engineering, pointed out the perception limitation that has persisted with 3D printing over time, something that has interested hobbyists and been viewed more as a weekend hobby. Her oversight includes hardware engineering across iPad, Mac, AirPods, and Apple Watch, and all materials innovation that goes into Apple products.

Bergeron says Apple’s approach was built on a foundation of titanium alloy and that it had to be fully recyclable. “A big thing that Sarah’s team challenged us on is that if we wanted to use 3D printing, we couldn’t regress from where we had been with titanium in our prior forging machine parts,” she says.

“It is not as simple as just grabbing titanium off the shelf that somebody may have brought back to their local recycler,” she says, before adding, “Uniquely to 3D printing, we have to optimise for the environment that the laser’s working in, which means we need to dial down the oxygen composition of that alloy so that when we go ahead and 3D print, it’s a safe environment.” While the technology has been around for a decade, Bergeron says it simply “wasn’t there” in terms of refinement, designs and structural capability.

Apple estimates more than 400 metric tons of raw titanium will be saved this year alone, with the switch to this new process. Historically, machining forged parts such as Apple Watch cases, was a subtractive process that required large portions of material to be shaved off. With 3D printing for the Watch Ultra 3 and titanium cases of the Watch Series 11, raw material input is halved compared to previous Apple Watch generations.

The complex process, particularly with 3D printing Apple Watch cases, is illustrated by Bergeron. “Most of us think about them as sort of hobbyist-type machines, but a couple of things would have been untenable for us. One is accuracy. In order to get something that’s as precise as the features inside Apple Watch, we had to figure out how small and fine we could print those features and then conversely, do it as quickly as possible so that we could actually make it cost-effective and energy effective,” she explains.

Apple eventually settled on 60 microns as the layer detail on the printing bed, and the process involves 900 different operations for each Apple Watch body. The inspiration has come from aerospace, where it is common practice to 3D print parts and retrofit them onto aircraft that are close to being put into service.

It wasn’t easy to get supply chains in sync. “Generally, they’re set up and then they run that way for a very long time. And what we’re asking for is a very big disruption, to change the system and do it a different way. And that does require a lot of overcoming inertia and obstacles,” says Chandler.

Unlocking the Apple 2030 target

Apple executives insist that in previous years, even a 10% increase in material efficiency would be considered an environmental win, but this leap forward is much more. Crucial, they insist, remains the fact that the latest generation Apple Watches with 3D printed cases, don’t look or feel any different to previous ones. The goal was to mature this technology to the place where they could take subtractive manufacturing, replace it with additive manufacturing.

This, Chandler insists, is the latest big swing in the Apple 2030 vision, one where the tech giant intends to be completely carbon neutral across all operations and product lines. In a conversation with HT earlier, CEO Tim Cook had called these targets “un-negotiable”. The baseline for the target calculations is set at 2015.

“It’s getting to the tough part. This is where we really need some unlocks, some incredible innovations, and this is one of those,” she explains. There is an understanding that manufacturing, products and renewable energy parity worldwide will get even more challenging in the final push, logistics being another element.

“We’re really trying to find things that we can unlock that others can then copy because ultimately, if the system changes, that’s how not just us but others will also decarbonise. It’s critically important to us that it’s a roadmap that others can follow,” says Chandler.

Some milestones on the Apple 2030 journey include the world’s first direct carbon-free aluminium in iPhones, starting with the last iPhone SE, a switch to the use of fully recycled cobalt for all batteries, 100% aluminium enclosure in iPad Pro and a 34% reduction in manufacturing carbon footprint, once the Mac mini shifted to Apple’s own M1 processors from Intel chips. The iPhone Air uses 80% recycled titanium in the device. The latest generation Mac mini is designed with more than 50% recycled materials. Additionally, the iPhone 17 Pro lineup, among other features, utilises a battery that contains 100% recycled cobalt and 95% recycled lithium.

“It does make things a little bit harder for us in the short term. Obviously, we believe it’s well worth it in the end. We really want to lay a foundation here that others can follow, and that this becomes the way that people make products. We’re the hard part, but we are relentlessly optimistic and doing really well relative to the 75% goal so far,” she adds.

Philosophy of making products

For Chandler, the philosophical pivot is straightforward but deceptively difficult to execute, and that’s where synergies with Bergeron’s team become crucial. They are clear that while environmental gains cannot come at the cost of a regressed user experience, longevity or the “joy” of owning an Apple product. “We want these products to be even better. for their environmental attributes. We want them to be better for the product, for the customer, for the planet,” she says.

This has been Apple’s internal north star for years, but 3D printing pushes that doctrine into a new domain — the idea is to find pockets of win-win, and the 3D printing method is one of those. A traditional fear within tech companies is that sustainability goals inevitably force trade-offs — this could mean weaker or less resilient materials, designs that may not be as effective, or compromises on finishing. Apple’s mandate flips that idea on its head. As Chandler puts it, the environmental attributes must make a product better. And that is where the company’s methodical approach comes through — choose points in a product where material innovation, carbon reduction and premium hardware all move in the same direction.

Bergeron takes the example of the iMac, which has fairly straightforward design cues, and as she says, the obvious thing to do is stamp it out of sheet metal.

“Because that’s high material utilisation, it makes sense for the size of the product. And so that’s in the toolkit and available to us and has been for a long time. Similarly, CNC machining of certain types of features. And now we have 3D printing at both a scale and an accuracy that makes sense. And so we continue to work through all of those interesting innovations, and it really allows both industrial designers and the mechanical engineers to come together where there’s no limit on the creativity of what we think we can do,” she says.

“We want the product to last as long as possible, and I think there’s an important caveat in there that we also want it to be in use as long as possible,” Chandler points out. Apple’s focus on that point includes software updates and also the trade-in programs for when a user wants to switch to another product or upgrade.

For Apple, there is big investment in the recycling and recovery of the materials that are in a product which a user is no longer using, and wants to replace with a new one. “It’s a really important tie because we can really truly close this loop and that’s the goal. Ultimately, if we want to build products using only recycled or renewable materials, we need those material loops to be closed,” she says.

And in the 2030 roadmap, each of these breakthroughs is not a one-off achievement but a prerequisite for the bigger picture — finding new manufacturing methods scaling recycled raw material supply, shifting to low-carbon logistics, and nudging a global manufacturing ecosystem that’s often set in its ways, away from comfortable, decades-old processes.

Creative palette: Shrinking or expanding?

There is a long-standing myth in the design world that sustainability shrinks the creative palette. Bergeron is adamant that the opposite is true — and 3D printing is proof of this. Historically, CNC machining set the boundaries; particularly if a curve could not be milled, designers simply could not sketch it. If an undercut couldn’t be achieved, it was erased at the industrial design stage. Engineers were taught early that gravity, cutter diameters and the physics of machining defined their imagination.

When HT asked Bergeron about how she views the palette structuring in the new manufacturing era, and how those frameworks are finalised internally, she called it the “perfect question that requires her and Sarah’s teams to work in a coordinated way.” That is a microcosm of Apple’s approach to trying to “solve the whole problem”.

With additive manufacturing at Apple’s scale, those constraints quietly fall away. As Bergeron tells us, her own engineering instincts “reset” when she sees students designing objects that traditionally only a 3D printer could make — geometries that were previously hypothetical. The constraints have loosened, not tightened. And that helps. For Apple’s product designs, this means the flexibility to redesign structures, shapes, or elements that improve antenna performance, as seen in the latest generation Apple Watch portfolio, and the ability to incorporate more features with water resistance capabilities.

This is perhaps a rare moment where sustainability, manufacturing innovation and design converge into the same lane. And Apple, understandably, is trying to accelerate.

Good for the planet, but do consumers notice?

The short answer: not yet — and that is by design. Chandler and Bergeron are aligned here, in the belief that material and manufacturing changes, such as the switch to 3D printing for the Watch Ultra 3 and Watch Series 11, should not feel like a regression. An Apple Watch must look like an Apple Watch, feel like an Apple Watch, and withstand the same durability gauntlet. The environmental lift is immense, but the aesthetic must remain invisible.

The reality is consumers aren’t buying “a 3D-printed watch”; they’re buying a Watch Ultra or a Series 11 that happens to be manufactured in a radically different way. The finish, tolerances, colour uniformity, and even the manufacturing sequence on the factory floor remain identical to those of the CNC-machined cases from previous years. From the assembly line’s perspective, the new casing has to behave exactly like the old one.

“There’s certainly a big door opening up there for, you know, even higher quality and interesting designs,” says Bergeron, and points out how deeper water resistance and better antenna performance on the Ultra benefit directly from additive manufacturing of 3D printing.

These aren’t marketing bullet points, but they underline iterative improvements Apple introduces with generational updates. For now, customers may not “see” a change in the Watch Ultra 3 compared with the generation before, but it is only a matter of time before lighter materials and builds, sturdier structures that hold up well in case of an accidental drop, and overall refinement, will be very noticeable. Apple’s plan is to quietly rewrite how premium devices are built, without consumers needing to adjust their expectations.