03:03

Pakistan’s food crisis: Clashes erupt over distribution of free government wheat flour during Ramzan

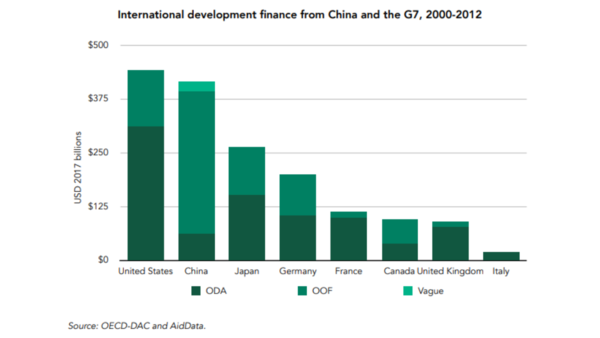

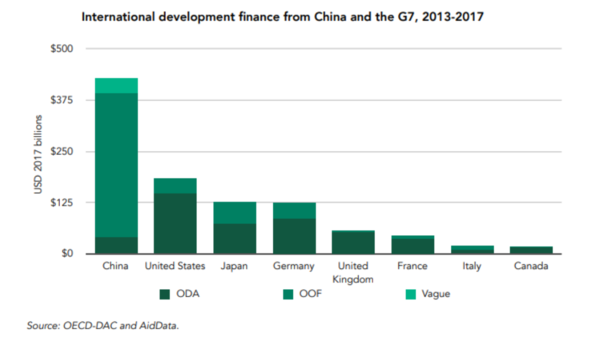

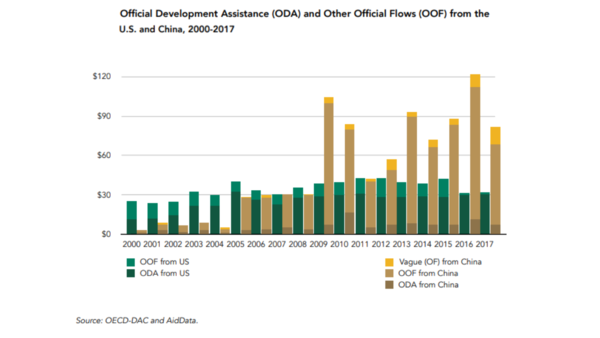

With annual international development finance commitments hovering around $85 billion a year, China now outspends the US and other major powers on a 2-to-1 basis or more. It is doing so with semi-concessional and nonconcessional debt rather than aid, according to a report by AidData.

Pakistan drowning in debt

Since the introduction of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, China has maintained a 31-to-1 ratio of loans to grants and a 9-to-1 ratio of Other Official Flows (debt) to Official Development Assistance (aid).

Pakistan is the 7th largest recipient of Chinese OOF (around $28 billion between 200o-17) and the 6th largest recipient of ODA (roughly $4 billion between 200o-17).

According to International Monetary Fund data, China holds roughly $30 billion of Pakistan’s $126 billion total external foreign debt. The cash-strapped nation is finding it hard to even pay the interest on the debt.

BRI projects stuck in limbo

The number of “mega-projects” —financed with loans worth $500 million or more—being approved by China each year tripled during the first five years of BRI implementation.

Pakistan is host to 71 BRI projects (second highest globally after Cambodia, which has 82) with a total value of around $27.3 billion.

However, nearly 10 of these projects (worth around $6 billion) have been marred with scandals, controversies, or alleged violations; another 4 have claims of corruption or other types of financial wrongdoing, which have delayed implementation.

A total of 7 projects (worth roughly $2 billion) have already been described as “underperforming”.

Steep interest, collateralisation

The increasing levels of credit risk have created pressure for China to introduce stronger repayment safeguards.

Chief among these safeguards is collateralisation, which has become the linchpin of China’s implementation of a high-risk, high-reward credit allocation strategy.

In the interest of securing energy and natural resources, China has rapidly scaled up the provision of foreign currency-denominated loans to resource-rich countries that suffer from high levels of corruption. These loans are collateralised against future commodity export receipts to minimise repayment and fiduciary risk and priced at relatively high interest rates (nearly 6%) — other lenders offer funds at around 3%.

‘Debt may be used as coercive leverage’

The US recently said it was “deeply concerned” that the OOF loans being given by China to Pakistan and Sri Lanka may be used for coercive leverage in case they fail to pay back their debts.

“Concerning Chinese loans to countries in India’s immediate neighbourhood, we are deeply concerned that loans may be used for coercive leverage,” said Donald Lu, assistant secretary of state for South and Central Asia. “We are talking to India, talking to countries of the region about how we help countries to make their own decisions and not decisions that might be compelled by any outside partner, including China,” Lu said.

Beijing has already taken Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port on a 99-year lease as Colombo failed to service its debt by China.

Pakistan, too, is crumbling under enormous debt. While debt per se is not a bad thing, China’s debt comes at a higher cost which makes interest payment difficult for struggling economies like Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

Under-reporting of debt

The majority of China’s overseas lending was directed to sovereign borrowers (i.e., central government institutions) during the pre-BRI era, but nearly 70% is now directed to state-owned companies, state-owned banks, special purpose vehicles, joint ventures, and private sector institutions.

These debts, for the most part, do not appear on government balance sheets in LMICs.

However, most of them benefit from explicit or implicit forms of host government liability protection, which has blurred the distinction between private and public debt and introduced major public financial management challenges for LMICs.

As a result, 42 LMICs now have levels of debt exposure to China in excess of 10% of GDP.

These debts are systematically underreported to the World Bank’s Debtor Reporting System (DRS) because, in many cases, central government institutions in LMICs are not the primary borrowers responsible for repayment.

It is estimated that the average LMIC government is underreporting its actual and potential repayment obligations to China by an amount that is equivalent to 5.8% of its GDP. Collectively, these underreported debts are worth approximately $385 billion.

(With inputs from agencies)

Watch Pakistan: Finance Minister Ishaq Dar warns of inflation spike amid crisis