BEIJING: An alleged Chinese surveillance balloon over the United States last week sparked a diplomatic furore and renewed fears over how Beijing gathers intelligence on its largest strategic rival.

FBI director Christopher Wray said in 2020 that Chinese spying poses “the greatest long-term threat to our nation’s information and intellectual property, and to our economic vitality”.

China’s foreign ministry said in a statement to AFP that it “resolutely opposed” spying operations and that American accusations are “based on false information and sinister political aims”.

The United States also has its own ways of spying on China, deploying surveillance and interception techniques as well as networks of informants.

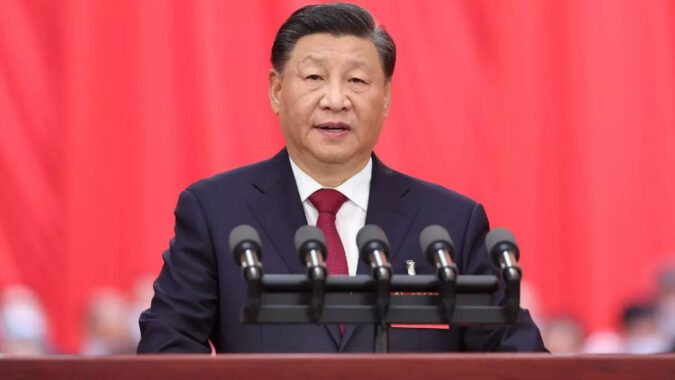

Former US president Barack Obama said in 2015 that his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping had promised not to conduct commercial cyber spying.

Subsequent statements by Washington have indicated the practice has continued.

Here are some of the ways Beijing has worked to spy on the United States in recent years:

The United States warned in a major annual intelligence assessment in 2022 that the Asian giant represents “the broadest, most active, and persistent cyber espionage threat” to the government and private sector.

According to researchers and Western intelligence officials, China has become adept at hacking rival nations’ computer systems to make off with industrial and trade secrets.

In 2021, the United States, Nato and other allies said China had employed “contract hackers” to exploit a breach in Microsoft email systems, giving state security agents access to emails, corporate data and other sensitive information.

Chinese cyber spies have also hacked the US energy department, utility companies, telecommunications firms and universities, according to US government statements and media reports.

Fears of the threat from Beijing have seeped into the technology sector, with concerns that state-linked firms would be obliged to share intel with the Chinese government.

In 2019, the US department of justice charged tech giant Huawei with conspiring to steal US trade secrets, evade sanctions on Iran, and other offences.

Washington has banned the firm from supplying US government systems and strongly discouraged the use of its equipment in the private sector over fears that it could be compromised.

Huawei denies the charges.

Similar anxiety over TikTok animates Western political debate, with some lawmakers calling for an outright ban on the hugely popular app developed by China’s ByteDance over data security fears.

Beijing has leaned on Chinese citizens abroad to help gather intelligence and steal sensitive technology, according to experts, US lawmakers and media reports.

One of the most high-profile cases was that of Ji Chaoqun, who in January was sentenced to eight years in a US prison for passing information on possible recruitment targets to Chinese intelligence.

An engineer who arrived in the United States on a student visa in 2013 and later joined the army reserves, Ji was accused of supplying information about eight people to the Jiangsu province ministry of state security, an intelligence unit accused of engaging in the theft of US trade secrets.

Last year, a US court sentenced a Chinese intelligence officer to 20 years in prison for stealing technology from US and French aerospace firms.

The man, named Xu Yanjun, was found guilty of playing a leading role in a five-year Chinese state-backed scheme to steal commercial secrets from GE Aviation, one of the world’s leading aircraft engine manufacturers, and France’s Safran Group.

In 2020, a US court jailed Raytheon engineer Wei Sun — a Chinese national and naturalised US citizen — for bringing sensitive information about an American missile system into China on a company laptop.

With the goal of advancing Beijing’s interests, Chinese operatives have allegedly courted American political, social and business elites.

US news website Axios ran an investigation in 2020 claiming that a Chinese student enrolled at a university in California had developed ties with a range of US politicians under the auspices of Beijing’s main civilian spy agency.

The student, named Fang Fang, used campaign financing, developed friendships and even initiated sexual relationships to target rising politicians between 2011 and 2015, according to the report.

Another technique used by Chinese operatives is to tout insider knowledge about the Communist Party’s opaque inner workings and dangle access to top leaders to lure high-profile Western targets, researchers say.

The aim has been to “mislead world leaders about (Beijing’s) ambitions” and make them believe “China would rise peacefully — maybe even democratically,” Chinese-Australian author Alex Joske wrote in his book, “Spies and Lies: How China’s Greatest Covert Operations Fooled the World”.

Beijing has also exerted pressure on overseas Chinese communities and media organisations to back its policies on Taiwan, and to muzzle criticism of the Hong Kong and Xinjiang crackdowns.

In September 2022, Spain-based NGO Safeguard Defenders said China had set up 54 overseas police stations around the world, allegedly to target Communist Party critics.

Beijing has denied the claims.

The Netherlands ordered China to close two “police stations” there in November.

A month later, the Czech Republic said China had closed two such centres in Prague.

FBI director Christopher Wray said in 2020 that Chinese spying poses “the greatest long-term threat to our nation’s information and intellectual property, and to our economic vitality”.

China’s foreign ministry said in a statement to AFP that it “resolutely opposed” spying operations and that American accusations are “based on false information and sinister political aims”.

The United States also has its own ways of spying on China, deploying surveillance and interception techniques as well as networks of informants.

Former US president Barack Obama said in 2015 that his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping had promised not to conduct commercial cyber spying.

Subsequent statements by Washington have indicated the practice has continued.

Here are some of the ways Beijing has worked to spy on the United States in recent years:

The United States warned in a major annual intelligence assessment in 2022 that the Asian giant represents “the broadest, most active, and persistent cyber espionage threat” to the government and private sector.

According to researchers and Western intelligence officials, China has become adept at hacking rival nations’ computer systems to make off with industrial and trade secrets.

In 2021, the United States, Nato and other allies said China had employed “contract hackers” to exploit a breach in Microsoft email systems, giving state security agents access to emails, corporate data and other sensitive information.

Chinese cyber spies have also hacked the US energy department, utility companies, telecommunications firms and universities, according to US government statements and media reports.

Fears of the threat from Beijing have seeped into the technology sector, with concerns that state-linked firms would be obliged to share intel with the Chinese government.

In 2019, the US department of justice charged tech giant Huawei with conspiring to steal US trade secrets, evade sanctions on Iran, and other offences.

Washington has banned the firm from supplying US government systems and strongly discouraged the use of its equipment in the private sector over fears that it could be compromised.

Huawei denies the charges.

Similar anxiety over TikTok animates Western political debate, with some lawmakers calling for an outright ban on the hugely popular app developed by China’s ByteDance over data security fears.

Beijing has leaned on Chinese citizens abroad to help gather intelligence and steal sensitive technology, according to experts, US lawmakers and media reports.

One of the most high-profile cases was that of Ji Chaoqun, who in January was sentenced to eight years in a US prison for passing information on possible recruitment targets to Chinese intelligence.

An engineer who arrived in the United States on a student visa in 2013 and later joined the army reserves, Ji was accused of supplying information about eight people to the Jiangsu province ministry of state security, an intelligence unit accused of engaging in the theft of US trade secrets.

Last year, a US court sentenced a Chinese intelligence officer to 20 years in prison for stealing technology from US and French aerospace firms.

The man, named Xu Yanjun, was found guilty of playing a leading role in a five-year Chinese state-backed scheme to steal commercial secrets from GE Aviation, one of the world’s leading aircraft engine manufacturers, and France’s Safran Group.

In 2020, a US court jailed Raytheon engineer Wei Sun — a Chinese national and naturalised US citizen — for bringing sensitive information about an American missile system into China on a company laptop.

With the goal of advancing Beijing’s interests, Chinese operatives have allegedly courted American political, social and business elites.

US news website Axios ran an investigation in 2020 claiming that a Chinese student enrolled at a university in California had developed ties with a range of US politicians under the auspices of Beijing’s main civilian spy agency.

The student, named Fang Fang, used campaign financing, developed friendships and even initiated sexual relationships to target rising politicians between 2011 and 2015, according to the report.

Another technique used by Chinese operatives is to tout insider knowledge about the Communist Party’s opaque inner workings and dangle access to top leaders to lure high-profile Western targets, researchers say.

The aim has been to “mislead world leaders about (Beijing’s) ambitions” and make them believe “China would rise peacefully — maybe even democratically,” Chinese-Australian author Alex Joske wrote in his book, “Spies and Lies: How China’s Greatest Covert Operations Fooled the World”.

Beijing has also exerted pressure on overseas Chinese communities and media organisations to back its policies on Taiwan, and to muzzle criticism of the Hong Kong and Xinjiang crackdowns.

In September 2022, Spain-based NGO Safeguard Defenders said China had set up 54 overseas police stations around the world, allegedly to target Communist Party critics.

Beijing has denied the claims.

The Netherlands ordered China to close two “police stations” there in November.

A month later, the Czech Republic said China had closed two such centres in Prague.